Controlling emotion mindfully

Mindfulness and Emotion Control

Most people either forget, or don’t know, that our complex human brains can be subdivided into the ‘old brain’ (sometimes known as the emotional brain) and the ‘new brain’ (sometimes called the rational brain). The old brain is genetically engineered to keep us alive – it reacts almost instantaneously to perceived threats or dangers by creating strong emotional responses (fear, anger, anxiety etc.) and this defence mechanism has served us well in our hunter/gatherer past. The ‘fight or flight’ response is a typical, emotionally driven response to danger, in which our bodies are equipped, almost instantaneously and without conscious control, with the resources needed to fight the danger or flee from it. Equally, the urge to mate and the pleasure we get from skin-to-skin bodily contact are governed by other, equally powerful, genetically driven, hard-wired imperatives.

While this type of threat response was very useful to our survival on the African savannah tens of thousands of years ago, these heuristic algorithms are less suitable for handling the majority of our 21st Century, modern day interactions.

The powerful emotions we experience when our fight or flight responses are activated can sometimes be so overwhelming that the rational brain does not have an opportunity to process what is happening and therefore we are not always able to react to our feelings wisely. For example: most of us will experience road rage at some point in our lives and it is sometimes difficult or impossible to resist the urge to physically or verbally attack other road users. Even when we are given time and space, and know rationally and consciously that the emotions we are experiencing (and any consequent behaviours) are not appropriate to our current circumstances, we often still struggle to cope with the physical effects of the massive chemical changes that have taken place in our brains and bodies.

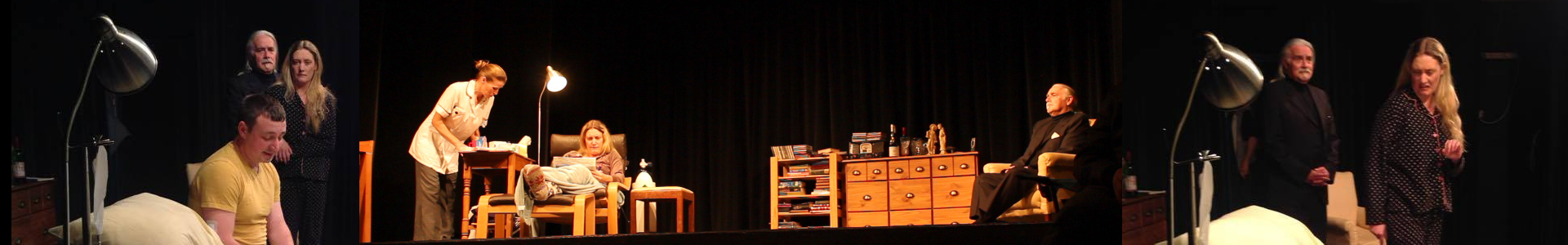

I used to find this when, as a professional actor, I was auditioning for roles. The only way an actor is validated is by the work he or she gets. No-one asks to see your degrees or diplomas, you are asked to stand in front of a panel of people to show what you can do and convince them to give you the job. It dawns on you that these few people control not only one’s future, but also one’s standing within the acting profession. No wonder then, that these occasions can be incredibly fraught. The degree of importance placed on making that good impression – and the anxiety resulting from that perception – alerts the emotional brain to do what it always does when we are going into a potentially dangerous situation. We are pumped full of adrenaline – and the centred and mellifluous Cassius we rehearsed so spectacularly well in front of the mirror at home, descends into a squeaky, tense and breathless parody of Shakespearean performance. We suddenly find ourselves physically equipped to leap off the stage, punch the casting director on the nose and run like hell. This will, in all probability, not get us the job.

While my more modern rational mind knew that these emotions were counterproductive, there seemed to be nothing I could do to stop the overwhelming anxiety I was experiencing. In fact, it took me a very long time to learn a range of psycho-physical techniques to override my natural responses to the disabling stage fright I was confronted with at every casting session. It is likely that you may have experienced similarly disabling emotions when faced with job interviews – or when being asked to give a presentation or talk to peers or colleagues.

Be aware that when in the grip of an overwhelming emotion, you are unlikely to react rationally. Remember ‘road rage’? However, there are even more sinister factors that might come into play. The fact that our emotional brain is hardwired to react to threat provoking stimuli has been seized on and used, very effectively, by the media. They know that we are more likely to respond to, and remember, threatening situations, bad news, violence and natural disasters. Stories that provoke us to experience fear, anxiety and anger sell newspapers and make broadcasts more memorable. This is why earthquakes, plane crashes, predatory paedophiles, bridge collapses and terrorism grab our attention – and good news is relegated to an inner page or the closing few lines of a news broadcast. Knowing this, media organisations are able to effectively manipulate us into experiencing fear, anger and anxiety – and some with a specific political agenda can ‘push our buttons’ to get us to react – sometimes quite unwarrantedly – to stories that do not even need to be accurate.

We find certain media outlets focusing on race, immigration, gender and sexuality – taking advantage of our innate cognitive abilities to discriminate on the basis of religion, sex, culture or colour – to engender a profound fear of other human beings who may be visibly or culturally different to us. We are encouraged to be angry at scarce resources being allocated to ‘them’ rather than to ‘us’, and invited to imagine the collapse of our own culture and the prospect of being swamped by alien invasions, strange cultural practices and suspect religious beliefs. The fact that most of these scenarios are easily debunked with a modicum of research and rationalisation can often be easily lost in the overwhelming range of emotions engendered by these stories.

It may not be your fault that you react to immigrants, asylum seekers or people who are different from you with discriminatory behaviours based on negative assumptions raised by the deliberate and planned activation of your threat recognition system. We do not choose to live in the brains we have, we tend to ‘find ourselves here’ and then have no option but to do the best we can with what we have. However, we do have the ability to choose to examine our feelings and behaviours and find out where they come from, how they were engendered and if they are valid and helpful, a distracting hindrance or something that may have been instilled into us by those who do not have our best interests at heart.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is the act of directing one’s attention, non judgmentally, to the present moment. We are encouraged to simply observe our senses, emotions and thoughts without making any value judgements about their provenance or authenticity. Mindfulness originated within the Buddhist tradition, but has since been validated as a remarkably effective tool for the management of emotions, pain and maladaptive thought processes. Simply noticing that you are anxious or angry, for example, observing your feelings with curiosity and compassion, can diminish the power of anger or anxiety to influence your behaviour. Practising mindfulness is not easy – but regular use can lead to improvements in both physical and mental health and can give us a great deal of insight into how our feelings may adversely impact on our behaviours.

Reading a tabloid story about asylum seekers being housed in vast mansions at the taxpayers expense while army veterans suffering from PTSD remain on housing lists may well push the buttons that activate the emotional mind and we could experience anger. Equally, in the employment arena, a disparaging comment from a co-worker or colleague may instill the same feeling. Mindfulness allows us to deal with it in more effective ways.

It can be helpful for you to ask yourself several times during your waking hours, “…what is my relationship to the present moment?” It is useful, when reading a newspaper or watching TV to realise when your ‘threat buttons’ are being pressed, by whom and for what purpose. Mindfulness is also where the rational and emotional mind overlap – it is where we are when we are wise, observing and non-judgmentally contextualising our emotional responses with rational thought.